Working with branches

This part has a small setup stage. Run 04_setup.sh if you want to follow along.

Branching is one of the topics where git shines. Git allows for lightweight branching and therefore for easy experiments. We will not go into discussion about branching strategies. This is something your team has to decide and find out. However, if you want to read up, have a look at this article by Martin Fowler about Patterns for Managing Source Code Branches.

Creating a branch

All you need to do to create a branch in git is use the

git branch branchName command. It will create a second ref

entry, named like your branch name and put the current commit hash into.

If you use git branch without providing it with a branch

name it will list your branches.

$ ls -l

total 0

-rw-rw-r-- 1 martin martin 0 Jul 17 00:19 file1

$ git branch

* main

$ git status --shortWe are on a main branch and one file is present. This file is tracked

and not changed as the git status output tells us.

We will now do three things, look at the content of HEAD, look at the

content of .git/refs/heads and the content of these files

before and after we create a branch.

$ cat .git/HEAD

ref: refs/heads/main

$ ls .git/refs/heads

main

$ cat .git/refs/heads/main

66eecc4254266d583817205576bab67ff44b91ee

$ git log --oneline

66eecc4 initial commitWe see our HEAD points to refs/heads/main and this

points to the first commit. Nothing new. Now we create a branch.

$ git branch mybranch

$ cat .git/HEAD

ref: refs/heads/main

$ ls .git/refs/heads

main

mybranch

$ cat .git/refs/heads/main

66eecc4254266d583817205576bab67ff44b91ee

$ cat .git/refs/heads/mybranch

66eecc4254266d583817205576bab67ff44b91eeGit created a second file in .git/refs/heads which is

called mybranch just as the branch name. The content is the

same as for the main file and the HEAD still points to the

main branch ref. Git basically creates a new pointer to the value of the

current HEAD. In our case to the tip of the main branch.

Switching Branches

Now we want to switch to our newly created branch. We have to options

git checkout and git switch. We will use the

newer git switch.

Again, let's look at the value of the HEAD before and after.

$ cat .git/HEAD

ref: refs/heads/main

$ git switch mybranch

$ cat .git/HEAD

ref: refs/heads/mybranchGit just points HEAD to the new ref. If we now commit, we will update

.git/refs/heads/mybranch and not the ref for main. That's

it. That is branching with git.

Of course there are switches for git switch to speed up

things.

| command | |

|---|---|

| git switch -c branchName | create branch and switch to it |

| git switch - | switch back to the branch you came from |

Renaming a branch

If a branch name is only a file name it surely can be renamed. Use

git branch -m newName to rename the branch you are on. Be

aware, renaming is a completely local operation. If you are

collaboration no one will know you renamed the branch in your repository

clone.

Conflicts

Before we talk about moving content from one branch to another. Let's quickly talk about conflicts. If a file is changed in more then one branch, chances are hight there will be a structural conflict. Git is not very clever in resolving those conflicts automatically. It will prompt you for help. A conflict looks like this:

base line

<<<<<<< HEAD

added on main

=======

added on mybranch

>>>>>>> mybranchFrom <<<<<<< HEAD to

====== is what we have on the branch we are applying this

change to. There is even a special diff format:

diff --cc file1

index 5c32171,e6bb0bc..0000000

--- a/file1

+++ b/file1

@@@ -1,2 -1,2 +1,6 @@@

base line

++<<<<<<< HEAD

+added on main

++=======

+ added on mybranch

++>>>>>>> mybranchCompared to the normal diff, this has two columns for change markers.

++means this is content which is new on HEAD and on mybranch_+means this is content which is present on HEAD but not on mybranch+_means this is content which is present on mybranch but not on HEAD

ReReRe

Git can help you resolving conflicts which may happen more then once.

This can be the case if you perform a rebase our must merge one source

into multiple branches. It is called rerere and stands for "Reusing

Recorded Resolution". You can activate it with

git config rerere.enabled true. Now git will record your

resolutions and will try to use them if it encounters the same conflict

again. Of course there is a lot more to it. Check out the documentation.

Moving content between branches

There are multiple ways moving content from one branch to another. We will look at cherry-pick, merge and rebase.

We can group them into two broad categories.

- Applying the diff of a commit. This creates a new commit, with a new tree but possibly the same blobs. Cherry-pick does that for one commit. Rebase for a whole branch.

- Keeping the commits intact. Merge does this. If needed merge creates a merge commit with a new diff to show the differences between both branches.

Cherry pick

To perform a cherry pick we need a commit to pick. Cherry-picks work best if the commit is atomic - meaning it should only do one logical change.

We will now create a cherry pickable commit on the main

branch and pick it into mybranch. But first, assume we

already did some work on mybranch, which is not on main.

$ git switch mybranch

echo 'some work on mybranch' > work

$ git add .

git commit -am 'add work on mybranch'

[mybranch b5d81b3] add work on mybranch

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 work

$ git switch main

echo 'important config' > config

$ git add .

$ git status --short

A config

git commit -am 'add configuration fix'

[main fe5ae35] add configuration fix

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 config

$ git log --oneline

fe5ae35 add configuration fix

66eecc4 initial commitWe now have the commit

fe5ae35d5b4e2ef782cd51652966b076f4f20a6c ready and want to

pick it into mybranch. We either can copy the commit hash,

type the first few digits or can use the help of

git rev-list to calculate it in the command directly.

git rev-list returns the commit hashes of all the commits

leading to the supplied endpoint, e.g. git rev-list HEAD

will print all the commits reachable from HEAD to the initial commit. If

supplied with the -n 1 switch it will only print the first

commit.

$ git switch mybranch

$ git rev-list main -n 1

fe5ae35d5b4e2ef782cd51652966b076f4f20a6c

git cherry-pick $(git rev-list main -n 1)

[mybranch e433fd3] add configuration fix

Date: Thu Jul 17 00:19:24 2025 +0200

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 config

$ git log --oneline

e433fd3 add configuration fix

b5d81b3 add work on mybranch

66eecc4 initial commit

$ git diff e433fd3f7044a00e98850187eeb19fdf0dfbe1c7..fe5ae35d5b4e2ef782cd51652966b076f4f20a6c

diff --git a/work b/work

deleted file mode 100644

index 4efabd5..0000000

--- a/work

+++ /dev/null

@@ -1 +0,0 @@

-some work on mybranchAs we can see, we created a new commit on mybranch. This

commit has a unique commit hash, the parent commit and the tree in the

commit differ from the one on main.

Merges

Now let's perform a simple merge. By default git does either a

ort 3-way merge or a fast-forward merge if possible. We

will first have a look at the ort strategy which replaced

the recursive strategy recently as default.

Merging is done with the git merge command and can be,

if needed, aborted with git merge --abort.

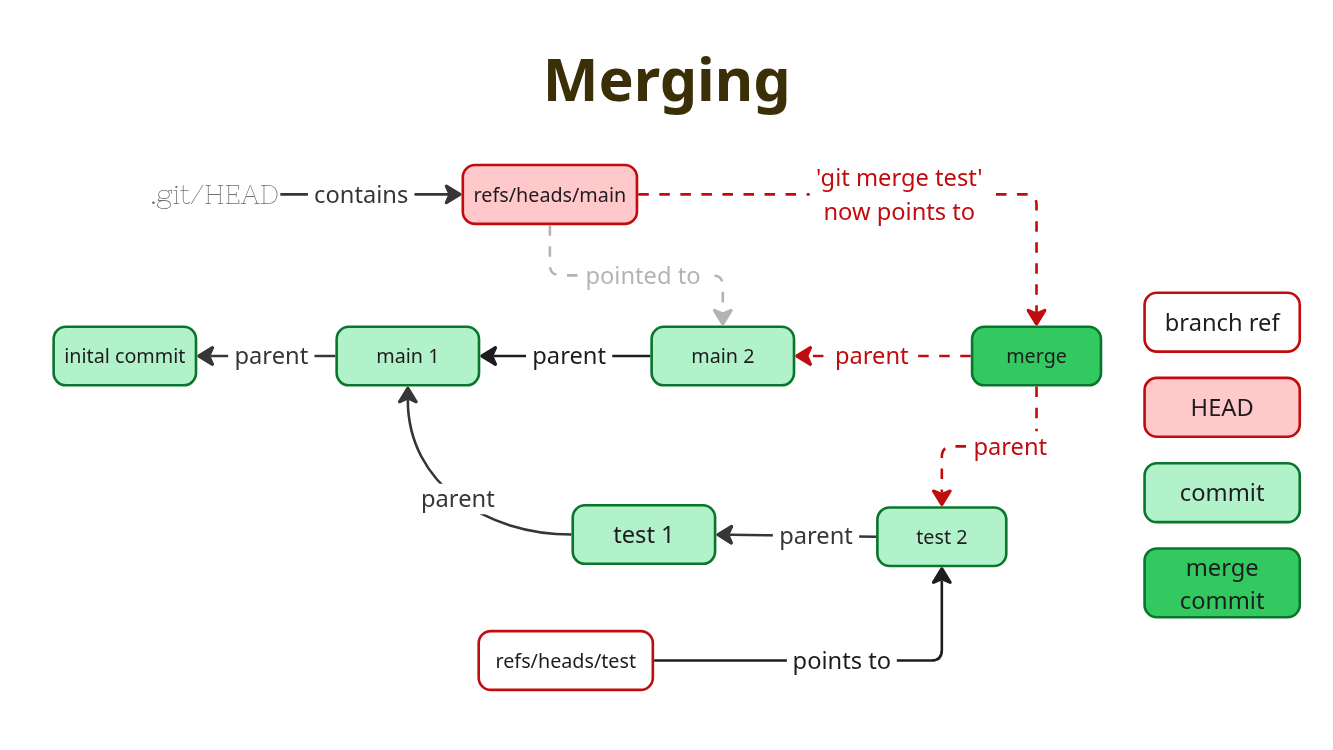

ORT Strategy

The ort strategy takes two heads and resolves them with

a 3-way merge algorithm. It can take various arguments, including

arguments like ignore-space-change and similar whitespace

aware modifiers. You can read it up here: Merge Strategies.

This strategy is uses when the two heads have diverged, meaning each

head points to commits the other one is not aware of.

Lucky for us, we have such a case. We will now merge the mybranch into main, look at the commit and at its diff.

$ git switch main

$ git merge mybranch -m 'merge mybranch'

Merge made by the 'ort' strategy.

work | 1 +

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

create mode 100644 work

$ git show

commit eebc1321afa3f47fcb249180e296ee620dd423c8

Merge: fe5ae35 e433fd3

Author: maschmi <maschmi@maschmi.net>

Date: Thu Jul 17 00:19:24 2025 +0200

merge mybranch

$ git cat-file -p eebc1321afa3f47fcb249180e296ee620dd423c8

tree 20e5c2a953d3f198e78d0c7f38004f6356340262

parent fe5ae35d5b4e2ef782cd51652966b076f4f20a6c

parent e433fd3f7044a00e98850187eeb19fdf0dfbe1c7

author maschmi <maschmi@maschmi.net> 1752704364 +0200

committer maschmi <maschmi@maschmi.net> 1752704364 +0200

merge mybranchAs we can see we created a merge commit. And interestingly this

commit has two parents and according to git show has not

changed anything - no diff present. A merge commit is a special commit.

It has two parents. The first parent is always the branch you are

merging into, the second is the source branch. git show

does not know which parent to compare to, to create a diff. There are

multiple options to show the diff, we will use the

-m\' flag. For more information runman git show`.

$ git show -m

commit eebc1321afa3f47fcb249180e296ee620dd423c8 (from fe5ae35d5b4e2ef782cd51652966b076f4f20a6c)

Merge: fe5ae35 e433fd3

Author: maschmi <maschmi@maschmi.net>

Date: Thu Jul 17 00:19:24 2025 +0200

merge mybranch

diff --git a/work b/work

new file mode 100644

index 0000000..4efabd5

--- /dev/null

+++ b/work

@@ -0,0 +1 @@

+some work on mybranchNow we see the change introduced by the merge commit.

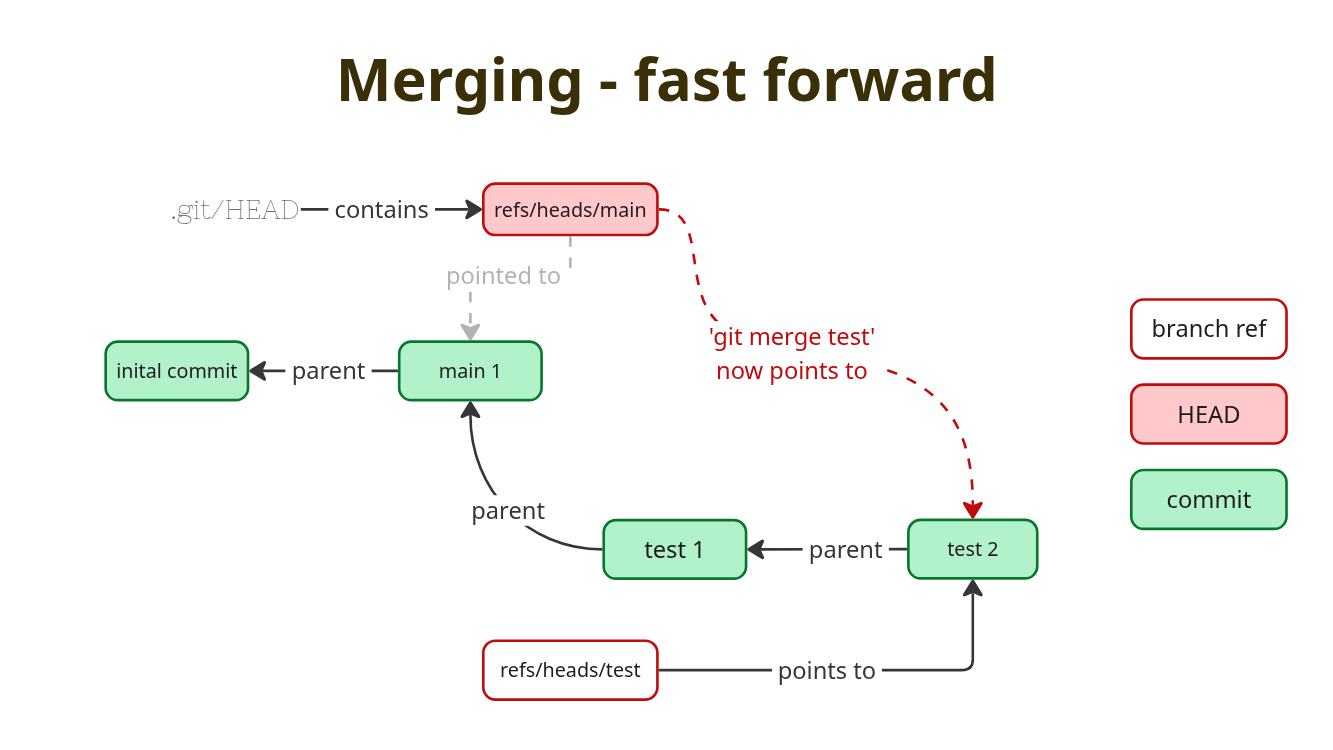

Fast Forward

A very easy way for git, and for us, is to do a fast forward merge. This only works, if the target branch we want to merge into, does not have any commits which are not already in the source branch we want to merge.

$ git switch -c fastforward

$ touch fast.forward

$ git add .

git commit -am 'add fast.forward'

[fastforward a24a54b] add fast.forward

1 file changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

create mode 100644 fast.forward

$ git switch main

$ git merge fastforward

Updating eebc132..a24a54b

Fast-forward

fast.forward | 0

1 file changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

create mode 100644 fast.forward

$ git log --oneline

a24a54b add fast.forward

eebc132 merge mybranch

fe5ae35 add configuration fix

e433fd3 add configuration fix

66eecc4 initial commit

b5d81b3 add work on mybranchWe see no merge commit. It was not necessary as the main

branch had nothing on it the fastforward not yet

contained.

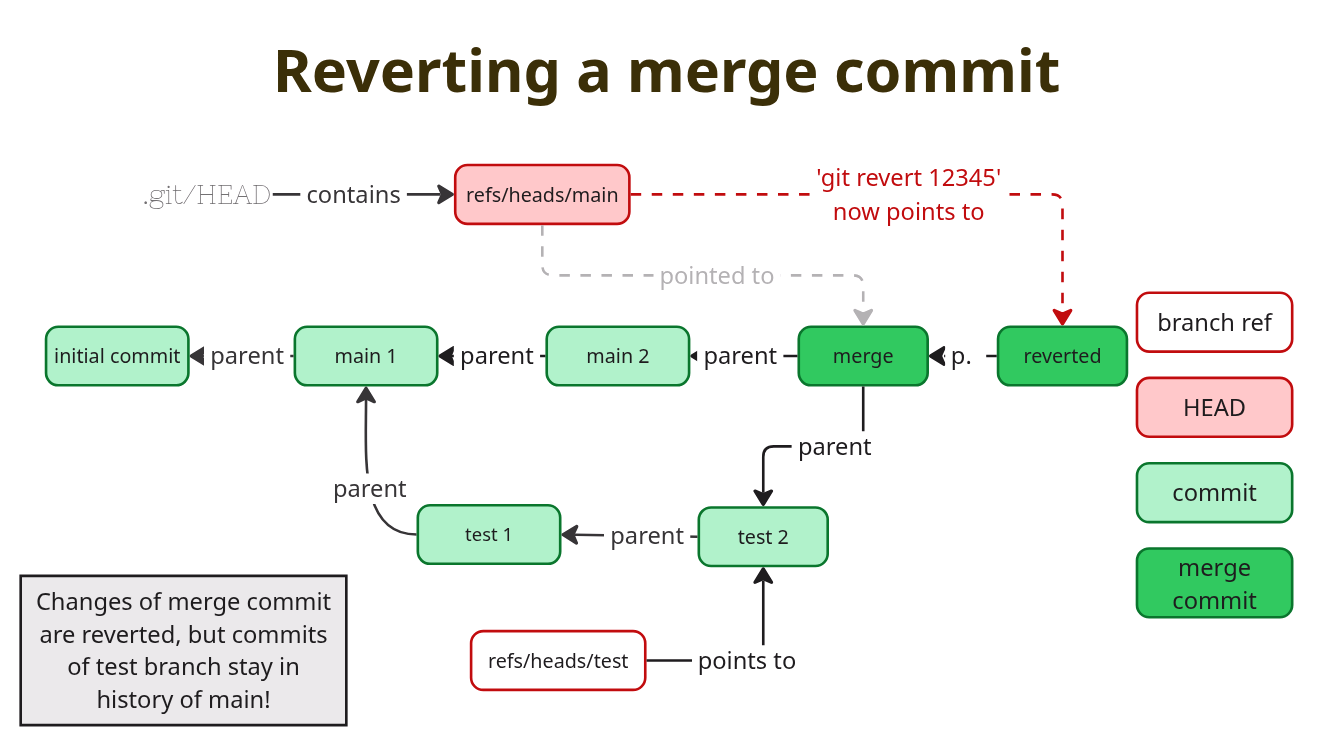

Reverting merge commits

Reverting merge commits can be tricky. The best way to revert is to

reset the target branch to the commit before the merge commit. We can do

a git revert for a merge commit and git will remove the

changes introduced by it. However, git will keep the commits from the

source branch in the history and will not apply the again when we merge

the same branch a second time.

Show me the whole history

Before we go to the rebase, let's have a look at a rather helpful log

format. We can tell git log with the --all

switch to show the log for all branches. When we combine this with

--oneline and `--graph' for graph, we get a nice graph of

the history. However, it sometimes is a bit confusing to read.

git log --all --graph --oneline

* a24a54b (HEAD -> main, fastforward) add fast.forward

* eebc132 merge mybranch

|\

| * e433fd3 (mybranch) add configuration fix

| * b5d81b3 add work on mybranch

* | fe5ae35 add configuration fix

|/

* 66eecc4 initial commitWe can read it from the top:

- HEAD points to main, fastforward and main point to the same commit

- the merge commit is also present on both branches, indicated by the

*in front of the commit hash - we can see what the merge commit merged

- now we find the commit the head of mybranch is on, this commit was

not done on either main, nor fastforward (

|and no*) - following it down towards the intial commit we can see other commits present only on mybranch or the other branches

- we also can see where mybranch was created

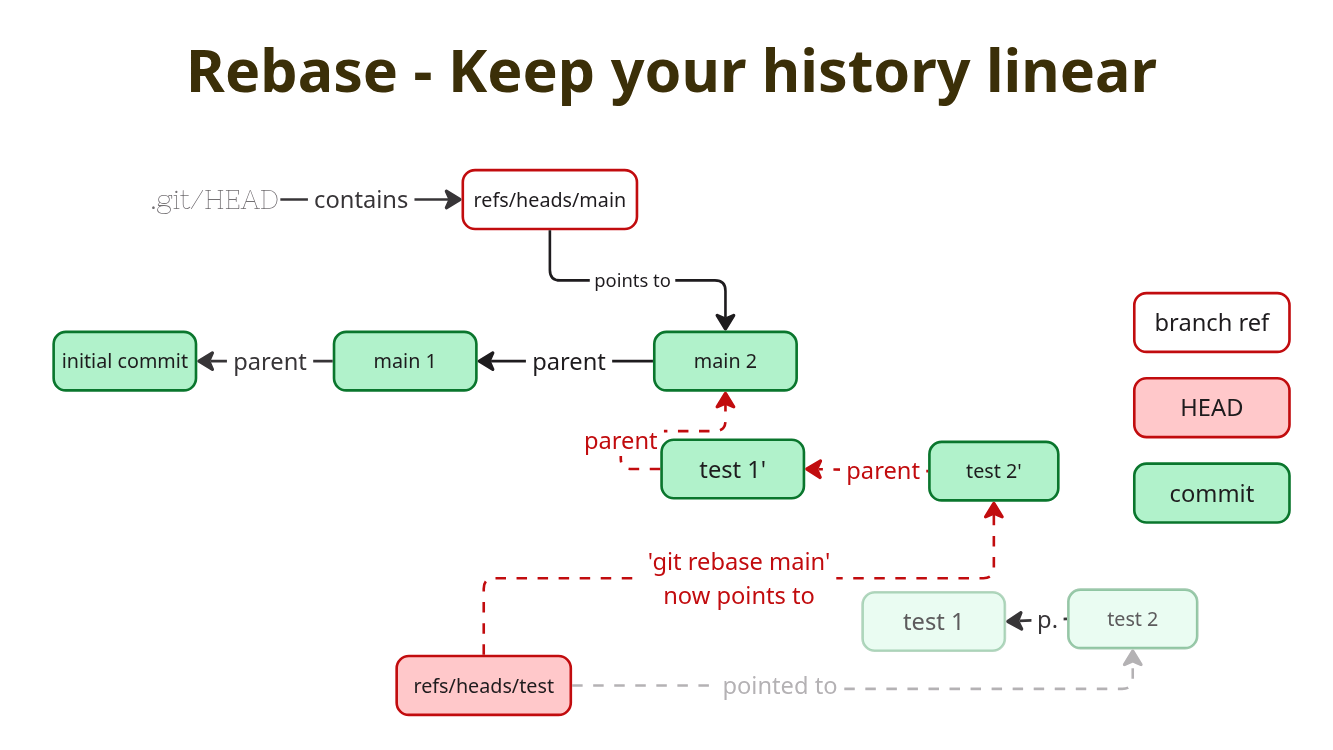

Rebase

A rebase works a bit differently compared to a merge. The first difference is: You rebase your current branch on top of the source branch. The second difference is: It will change the whole history of your current branch, every commit is changed. Remember the cherry-pick? Git applied the diff of the commit on your target branch, creating a new tree and a new commit. Rebase does this for all commits on your current branch. Starting with the oldest one. After the rebase you will have a linear history. But it will also be new and tell a different story.

Exercise

Jump over to the branches exercise to get familiar with merging, conflict resolution and rebasing.